El Paso’s Museum of History Celebrates Asian Community with the “Mountain of Gold: A history of East and Southeast Asian Cultures in El Paso del Norte, 1880s-1980s” Exhibition

Written by Kimberly Saenz | January 6, 2025

On the second floor of the El Paso Museum of History, two fu dogs cast in marble mark the entrance to the, “Mountain of Gold,” an exhibition which delineates the history of El Paso’s East and Southeast Asian communities. The Texas city of El Paso shares a border with Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, both referred to in this exhibition as the “Mountain of Gold” and the “Mountain of Silver.” Museum staff worked directly with the local residents to compile the artifacts, documents, and artwork, some of which lived amongst the families for generations. Research spanned a year of community outreach as the curators aim to transcend previous installations which focused primarily on the Spanish Conquest and other Eurocentric narratives.

The installation debuted in September of 2025, where a number of local restaurants and businesses sampled signature dishes from varying Asian cultures. With the extensive information gathered on the Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, and Vietnamese communities that make up El Paso’s diverse population, curators decided to extend the “Mountain of Gold’s” lifespan past the typical runtime of a year. It is currently the largest exhibition at the El Paso Museum of History and will remain open for a year and a half.

Despite the natural multiculturalism of the border city and the influx of immigration to both Mexico and El Paso throughout history, the distinction between Asian cultures and identities is and has been intentionally blurred. The goal for museum curators is to avoid the monolithic process of examining history, avoid using stereotypes associated with Asian cultures, and draw parallels between the harmful immigration policies and erasure tactics of then and now.

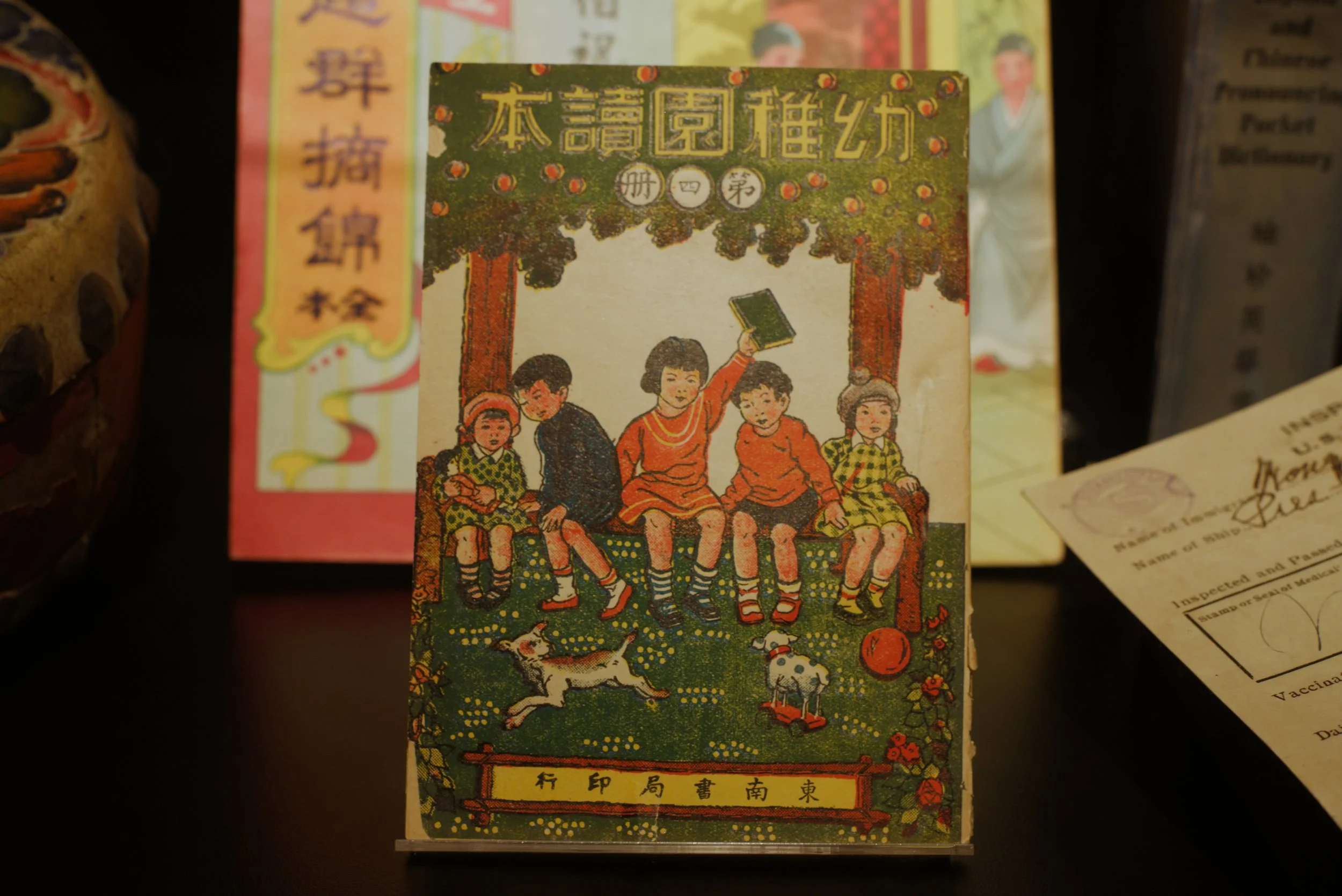

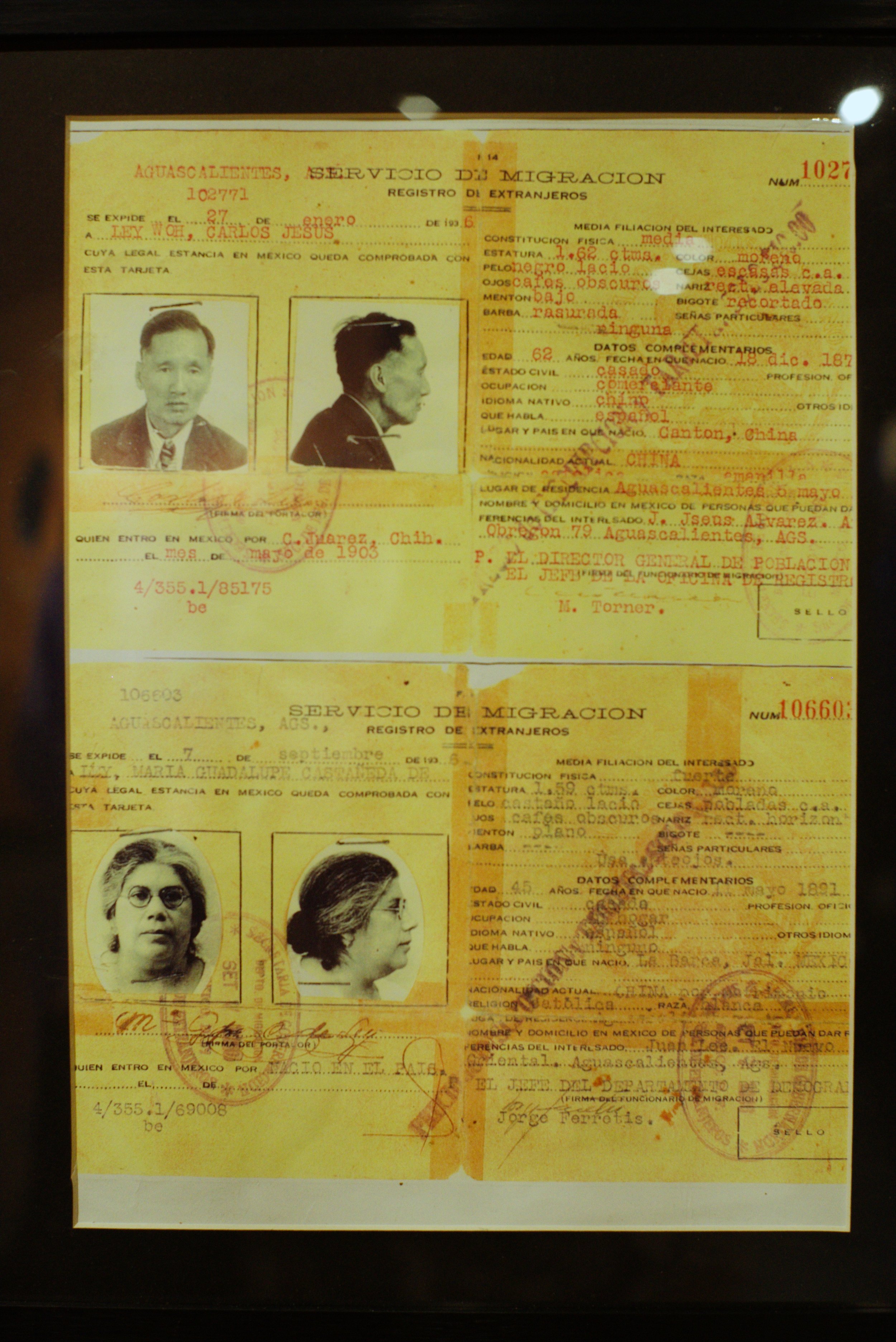

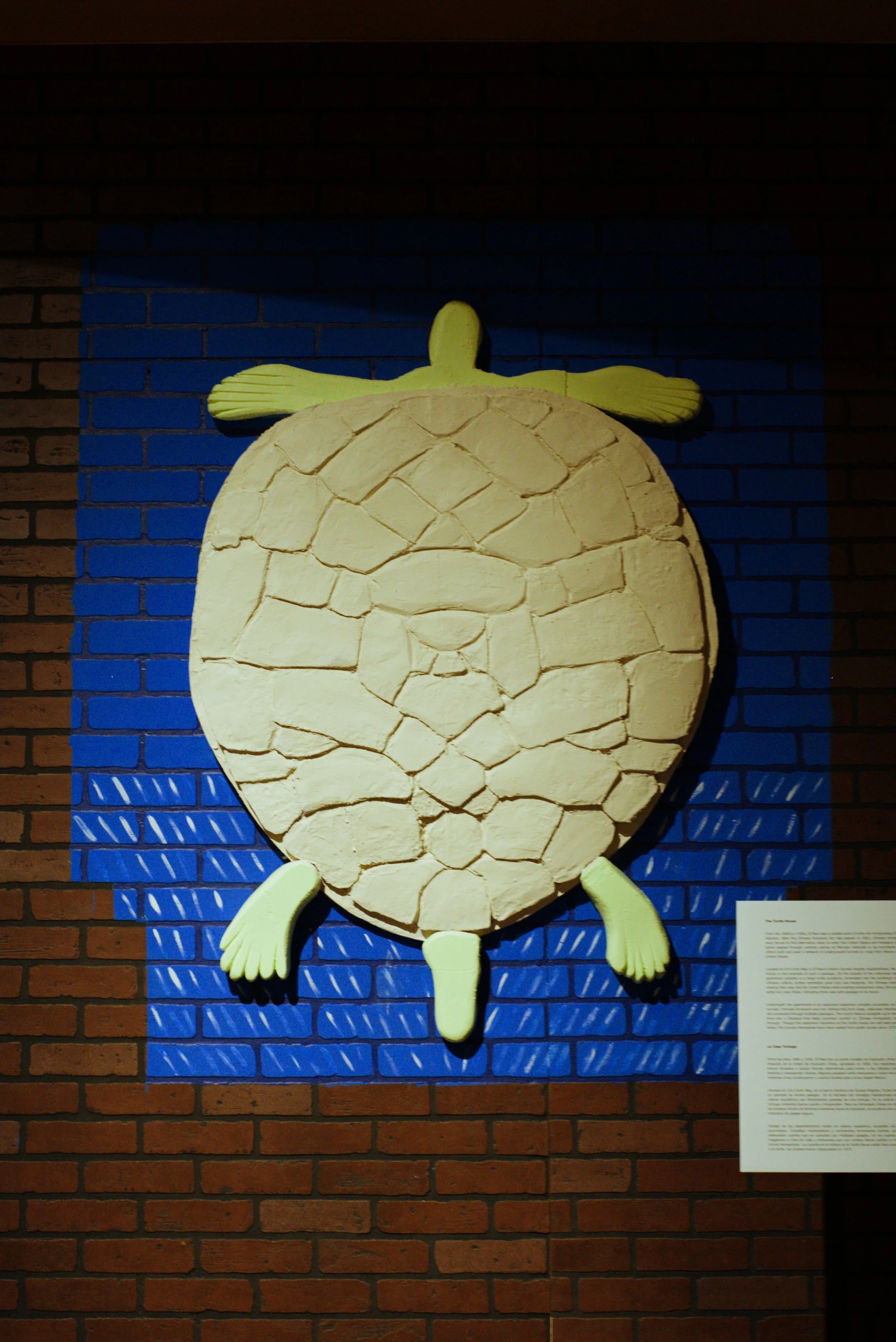

This vibrant corner of the museum displays furniture, life-sized and miniature duplicates of prominent grocery stores from the 1800s-1900s, handmade dolls, clothing, artwork, documents, and kitchenware from local families and businesses. Although known grocers, laundromats, and persons have been erased, built over, and displaced, documentation and the memory speaks to the prominence of the East and Southeast Asians who established themselves in Juarez and El Paso over the passage of time. The symbol of a turtle a safe-camp for the Chinese immigrants who used the underground tunnels beneath what is now known as the Turtle House to move safely between the United States and Mexico during tumultuous and targeted violence. The installation highlights the cause and effect of immigration, citing racial tensions and laws put into place, such as Japanese internment camps, miscegenation laws, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Precious tokens of ancestral lineage and motifs of cultural tradition were provided by living family members working in tandem with the museum to foster an indiscriminate demonstration of the multifaceted histories and accomplishments of El Paso’s Asian communities. Florals embroidered onto the multicolored silks of a lone binding shoe, no bigger than the palm of a hand, glimmer behind the glass of a display case lent to the museum by Linda Chew, a surviving member of the Chew family. The family settled in El Paso through opening several grocery stores and a wholesale outlet, but descendants are also known for participating in immigration advocacy and pursuing judicial law. A street sign in another section reads “Manila Dr.”, traced back to the land once owned by the Equid family, one of the first recorded Filipino families to settle in El Paso. These are only two examples of the family roots that make up El Paso’s network of cultures as well as its intersectionality.

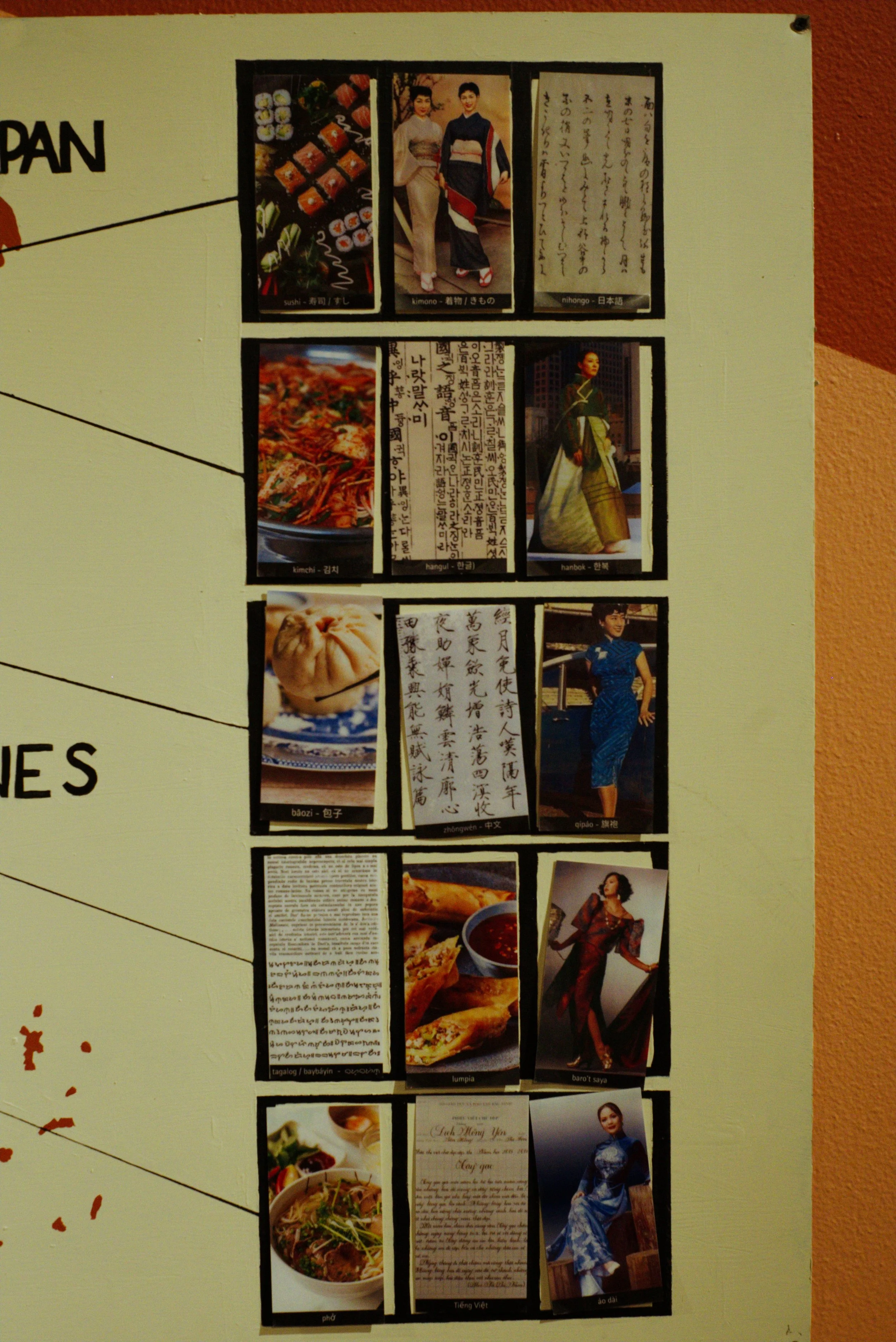

Museum visitors can discover noteworthy family lineages not only through black-and-white photographs, newspapers, and once buried ceramics but through the honest examination and challenging of the prejudices of the past and the present. The interactive section of the installation, constructed as a match game, indicates curators efforts to maintain a critical eye by asking visitors to confront their biases of Asian cultures. Pictures of cultural fashion, cuisine, and language are to be matched with their origin countries, returning dimension to the very real distinctions between Asian customs. The “No Soy Chino” section of the exhibit challenges the use of “chino” as a descriptor of any persons of Asian descent. It is a derogatory term still in use today in Mexican and Mexican American culture that flattens, dehumanizes, and perpetuates stereotypes. Through visiting this free exhibition, it is an opportunity to become informed, support the museum’s efforts, and set a precedent for mutual respect and multiculturalism.

Visit Their Website for More Info:

Website: epmuseumofhistory.org